In 2022, over 20,000 Lithuanians returned to their country of birth from abroad. A high quality of life coupled with a booming entrepreneurial ecosystem and a collaborative mentality has contributed to what investors are calling a “reverse brain drain.” Many of their minds reemerge in the country’s startup scene.

It was on a visit to Lisbon that I first heard someone refer to Lithuania as “a hidden gem” of Europe’s startup ecosystem. A recent trip to Vilnius convinced me they were right.

To further drive the inspiring transformation it has achieved since regaining its independence from the Soviet Union in 1990, Lithuania has been betting heavily on its homegrown tech startups.

Already home to three high-profile unicorns — online marketplace Vinted, VPN leader NordSecurity, and ad firm BCG — Lithuania is the fastest-growing ecosystem in the Baltics and Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) region. Last year, it reached €13.7bn in enterprise value last year, following a seven-fold growth between 2018 and 2023.

Housing nearly 900 startups, Vilnius alone accounted for 91% of the total value. Startups in the capital city raised 96% of the total funding (€281mn), enabling Lithuania to become the second biggest VC investment destination in Central and Eastern Europe, after Estonia.

“Lithuania is a startup itself.

Vilnius is also building Europe’s largest tech campus, set to open later this year.

But what lies behind the country’s exponential growth? I met with various ecosystem players to find out.

A startup (-friendly) mentality

Lithuania is “a startup itself compared to big countries,” according to Karolis Žemaitis, the country’s Vice Minister of Economy and Innovation.

“Because we don’t have that many resources and we don’t have that many people, we need to act on this mentality to be able to compete,” he explains.

This has fostered a risk-taking, make-do-with-less mindset, which is also reflected in the mentality of the startup ecosystem. “We have to be faster, we have to be bolder in some cases, and we have to be more adaptive to the global changes that are happening,” Žemaitis says.

This has built ecosystem resilience — a virtue of Lithuania not only throughout the era of the Soviet occupation, but also through its political and economic reinvention since the 1990s.

Despite the challenging economic impact of first the pandemic and then Russia’s full-scale invasion of nearby Ukraine, the Lithuanian ecosystem has maintained sustainable growth, capital flow, and a continuous increase in the number of startups.

For its part, the government has been cultivating a business-friendly environment. Last year for instance, a law amendment liberalised company share classes, which allows businesses to issue different types of preferred shares, in addition to being able to convert them into ordinary or other shares.

“We have to be careful in our approach to governmental interference in general,” adds Žemaitis. “Sometimes the government just has to let businesses do business.”

Compact size

Lithuania’s relatively small size and population plays in its favour.

The first thing I noticed, even after my first day in Vilnius, was how well-connected everyone was within the ecosystem. People weren’t simply referring to each other by their first names; they were enquiring about specific tech projects that they’re working on.

“It’s much easier to do things here, everyone knows everyone, and you’re one phone call or one WhatsApp message away from the person you want to speak with,” Žemaitis says.

This interconnectedness alongside a flat hierarchy system and an increasingly digitalised economy enables Lithuanian companies to do business faster.

Another benefit of operating within a smaller country is the focus on external markets right from the outset, which cultivates a global approach to growth. This strategy is one of the ecosystem’s success factors, according to Inga Langaite, CEO at startup association Unicorns Lithuania.

“When you start focusing on outside markets from day one, you build your business and its growth path differently,” Langaite says. “It’s more difficult to reorient your business from a focus on the home market to outside markets at a later stage.”

Sector diversity

The Lithuanian ecosystem is very diverse industry-wise. Its strengths range from fintech and ICT to laser technology and biotech.

Fintech, ICT, and GameDev

Fintech is a well-established sector in Lithuania. The country houses over 260 companies and serves as the HQ of multiple neobanks — including Revolut’s European operations — thanks to favourable licensing processes.

Cybersecurity is another. This is closely linked to NordSecurity, Lithuania’s second unicorn. Founded in 2012, the startup has been one of the drivers of the ecosystem’s creation. Behind the success lies “a can-do attitude and a strategy to do things fast,” says Ramūnas Markauskas, the company’s Head of Business Enablement.

Among the other legacy players and the oldest company of Lithuania’s thriving GameDev space is Nordcurrent — mostly known for the popular simulation mobile game Cooking Fever. Nordcurrent has bootstrapped its way to success, and generated €80mn in revenue in 2022.

“What differentiates us from other players in the field is that we are still a family-owned business, built on family finance,” says Simonas Stūrys, Head of Marketing at Nordcurrent. “This frees up our decisions as we don’t need to report to investor boards.”

Alongside Nordcurrent, there are 99 companies operating in the Lithuanian GameDev space.

Laser tech, healthtech, and deeptech

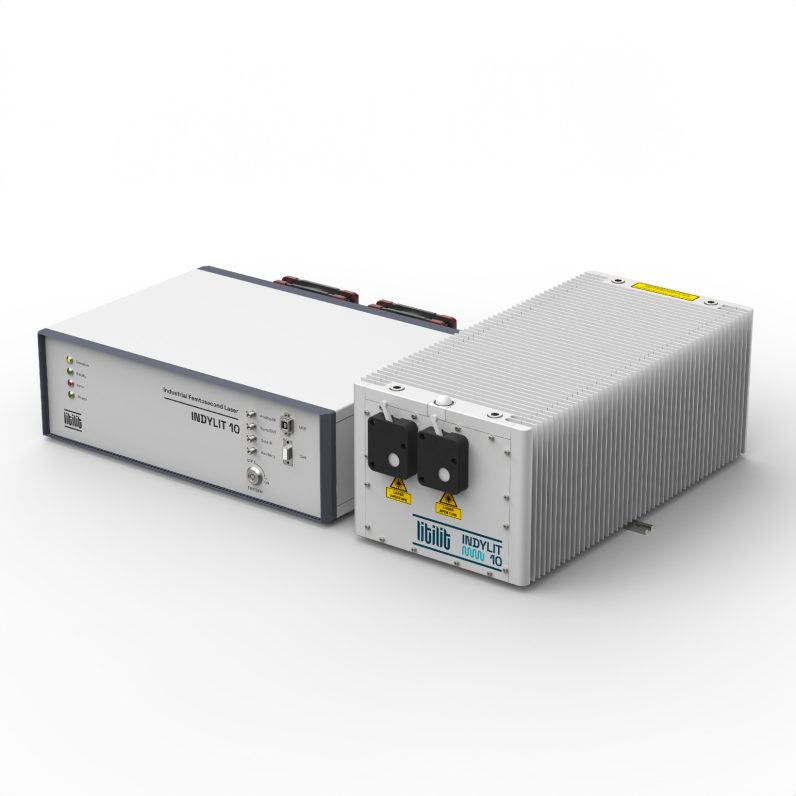

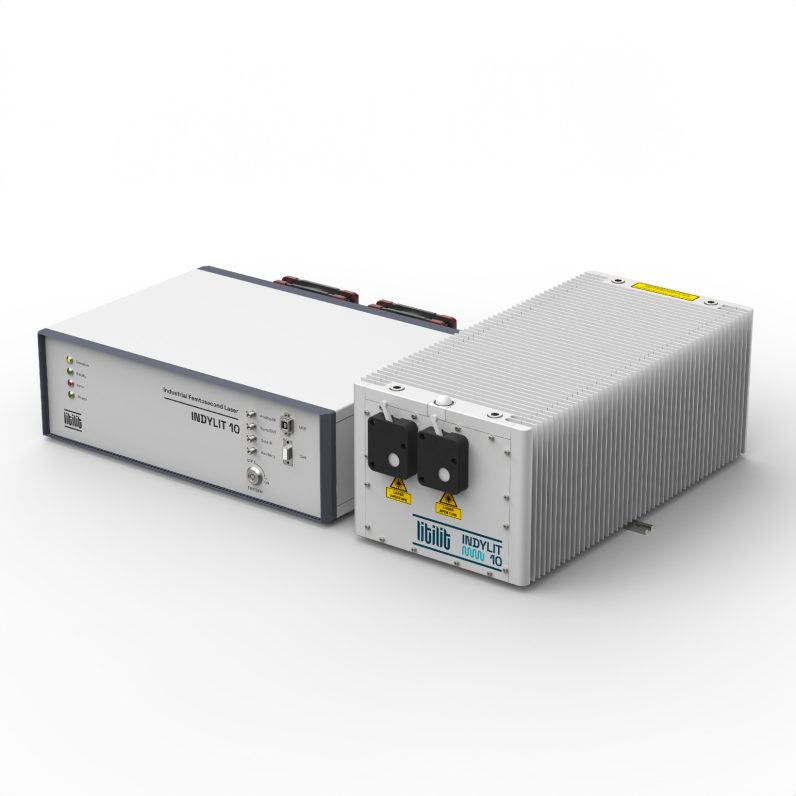

Laser tech is an industry with deep roots in Lithuania, dating back to 1966 when the first later was fired in the country. Among the most innovative companies in the space is Litilit.

Founded in 2015, the startup develops femtosecond lasers. According to Nick Gavril, co-founder and CEO of the company, their products represent “the latest frontier” in laser technology.

Thanks to a novel method for generating ultra short pulses, Litilit’s femtosecond lasers can enable high precision in material processing without changing the composition of the material itself — a common disadvantage of other laser technologies.

Gavril stresses another differentiating factor: the startup’s lasers are easy to use for experts and non-experts alike, enabling smaller and less specialised companies to include them in their processes.

Healthtech is also flourishing, propelled by the outbreak of the pandemic and political support for a strong life sciences sector.

Kilo Health is a major force in the space. Europe’s second fastest-growing company in 2021 and 2022, Kilo Health is a startup studio that co-founds and accelerates startups in digital healthcare. The company counts over 30 products and 6,500 customers worldwide. Vilius Cesnauskas, Chief Business Development Officer at Kilo Health, describes the key to the success as “being dreamers.”

Another standout is Walk15. On a mission to engage people in physical activity, the startup provides a platform and an app which enable users to participate in step challenges and use their steps to unlock exclusive discounts.

The company has built Lithuania’s largest fitness community. In March, it also launched a steps prescriptions pilot in collaboration with doctors in Vilnius.

Additionally, deeptech constitutes a booming sector — and one that “has been overlooked in the Baltics,” according to Dominykas Milasius, Investment Partner at Baltic Sandbox Ventures, which supports early-stage deeptech and life sciences startups.

Milasius says that the tide is gradually turning, stressing deeptech’s role in helping Lithuania become an engine of innovation, insulating it from economic uncertainty, and enabling alliances with NATO and other partners against rising geopolitical threats.

One notable startup in the industry is Pixevia, which develops AI and computer vision software for autonomous retail store operations. The company is behind the first autonomous store in Europe — an Iki supermarket in Vilnius.

The startup aims not only to boost customer experience, but also to optimise operations for retailers. According to Mindaugas Eglinskas, CEO at Pixevia, this ranges from inventory and assortment management to out-of-shelf alerts, ordering, and forecasting.

Talent attraction

Everyone I spoke with during my visit emphasised that talent attraction is the biggest challenge of the ecosystem. “Our talent need is much bigger than the supply,” Unicorns Lithuania’s Inga Langaite says.

Domestic talent

To expand its talent pool Lithuania is implementing multiple initiatives — both governmental and private — to up- or re-skill its existing workforce. Enabling training programmes that can lead directly to employment opportunities is a key part of the strategy. Such trainings include NordSwitch, the GameDev Camp, and the National Reskilling/Upskilling Programme.

The country has also implemented ongoing reforms in its education system to better prepare its future workforce by introducing IT and STEM courses on the curriculum.

International talent

When it comes to attracting international talent, Lithuania boasts increasing startup salaries, remote working opportunities, taxation benefits, and a high quality of life.

During my visit to Vilnius, I noticed myself that the city combines a slower-paced lifestyle, walkable distances, and a vibrant business environment.

The high quality of life alongside the ecosystem’s growth have also increased the number of Lithuanian repatriates, with 20,689 citizens returning in 2022.

“We’ve been experiencing a reverse brain drain.

Dominykas Milasius from Baltic Sandbox, a repatriate himself, sees this as “a systemic trend that is driving a lot of productivity.”

“We’ve been experiencing a reverse brain drain,” Milasius says.

“The maturity of our tech ecosystem has reached the point where people who previously worked on top tech products in the UK and Silicon Valley, or elsewhere, are now considering Lithuania as a real competitive option.”

A collaborative mindset and hunger for success

All the founders and ecosystem players I met emphasised that at the core of the Lithuanian startup scene lies a strong collaborative mindset — one that fosters the exchange of ideas, knowledge, lessons, and contacts.

I was impressed to find out that startups are investing in each other (Vinted, for example, has invested in Walk15). I was equally surprised when, during the Vilnius TechFusion Startup Awards, winning companies taking the stage kept mentioning the contribution of their fellow contestants.

“People still want to go the extra mile.

The community-based approach is a crucial aspect of Lithuania’s growth, according to Inga Langaite. “There is the mentality that if you are successful, you have to give back to your community and your country,” she says.

Langaite recalls the words of one founder in particular: “There’s no happiness if I’m the only one who’s successful and rich, but everyone else is not.”

Another key driver of growth is a hunger for success — a sentiment shared by everyone I spoke with, reflecting the ambition to actively shape Lithuania’s transformation.

“People are still hungry in a good way,” Karolis Žemaitis says. “People still want to do more, they want to go the extra mile — and that’s our competitive advantage.”

Žemaitis envisions Lithuania as one of Europe’s major startup hubs in the coming years.

Indeed, my visit to Vilnius showed me that Lithuania has both the ambition and the potential to rise further in the EU startup scene. It also revealed that its biggest strength is its people.